Table of Contents

Setting up SSL for your server may seem like a daunting task. In addition, why would you do it? What are the benefits? There are multiple, actually, with some of the most important ones being:

- It’s better for SEO. Back in 2014, Google announced they would start with giving HTTPS websites a little boost in the search results.

- It’s not slower than HTTP. In fact - it will even be faster with HTTP2 enabled. Check the “Is TLS Fast Yet?” website for details.

- It’s free. Ok, it’s not free if you want that spiffy, large green browser bar for your customer. If you are happy enough with a green lock (in Google Chrome at least), it’s free.

- You can automate it! Which is especially great when you manage multiple servers with multiple SSL certificates.

In this post we’ll setup an Nginx configuration in such a way that you will get an A+ rating on the Qualys SSL Labs test. If you want to follow along with this blog, you’ll need the following things already set up:

- A server

- A domain name pointing to that server

- Some generic Linux knowledge

tl;dr: If you just want to see an SSL Labs A+ rated Nginx configuration, check out my Github repo. This is the file I’ll be creating throughout this blogpost.

Setting up the server

Spinning up a test server somewhere is really easy these days. If you don’t have any within reach, be sure to check out providers such as DigitalOcean, AWS or Google Cloud. Though you will have to provide your payment details, they all provide free server time that you can use for testing.

If you just now setup your server, point your domain name to its public IP address. Keep in mind that DNS propagation might take a while.

Throughout this post I’ll be using Nginx on a CentOS 7.2 machine running on DigitalOcean. I’ll setup an A+ rated server for the domain example.com.

Getting a SSL certificate

Three types of certificates exists;

- Domain Validation (DV). Is often free and can be acquired through a simple domain/e-mail validation check.

- Organization Validation (OV). The CA will do some minimal checking on the company that requests the certificate (such as: does the company really exist?).

- Extended Validation (EV). The CA will do a lot of checking on the company that requests the certificate.

The thing about all three types is: they are equally secure from a cryptographic perspective. SSL Labs doesn’t consider the type of certificate you have for their rating.

For this setup we can get a free DV certificate. Different CAs exists where you can get one for free - I used StartSSL.com. Of course, if you want to use another CA, that should be perfectly fine.

We create the Certificate Signing Request (CSR) with the following openssl command:

openssl req -newkey rsa:2048 -nodes -keyout example.com.key -out example.com.csr

You can execute this command wherever you like - it doesn’t have to be on the server that you are configuring with SSL. Just make sure the created Private Key is not comprised, and that you have a recent version of OpenSSL installed.

Forward your CSR to your CA and download the certificate. Put the certificate for your server and the intermediate certificate in one .crt file. For all future configuration: I will be storing all the certificate files in the /etc/ssl directory. My certificate is stored as /etc/ssl/example.com/crt.

Installing Nginx

At the time of writing, Nginx version 1.10 is the stable version. Installing Nginx is easy. First, setup the nginx repository on your server by adding the following configuration to the /etc/yum.repos.d/nginx.repo file:

[nginx]

name=nginx repo

baseurl=http://nginx.org/packages/centos/$releasever/$basearch/

gpgcheck=0

enabled=1

Of course, if you are not running CentOS, but sure to following the Nginx installation guide for your OS. Next, we can install and turn on Nginx:

yum install nginx systemctl

start nginx

Now, go to the public IP address if your server from your browser. You should be welcomed by the not-so-welcoming welcome page of Nginx. If you do not see this page, make sure your firewalls are setup correctly and that your server is visitable from the internet.

Let’s set up a minimal configuration for example.com. We save the following configuration in the /etc/nginx/conf.d/example.com.conf file:

server {

listen 443 ssl;

server_name example.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/example.com.crt;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/example.com.key;

ssl_protocols TLSv1 TLSv1.1 TLSv1.2;

location / {

root /usr/share/nginx/html;

index index.html index.html;

}

}

If you are following along: be sure to replace the hostname with your own. In the configuration, we reference the private key that we created ourselves and the certificate that we received from the CA. We re-use the default HTML files Nginx comes with and stores in /usr/share/nginx/html. To apply this configuration, restart Nginx with the following command:

systemctl restart nginx

Quick note: since version 1.9.1 the default ssl_protocols value is the one specified in the above configuration so technically, we don’t need it in our own configuration. However, I still like to add it for transparency and in case we (accidentally) run an older version of Nginx.

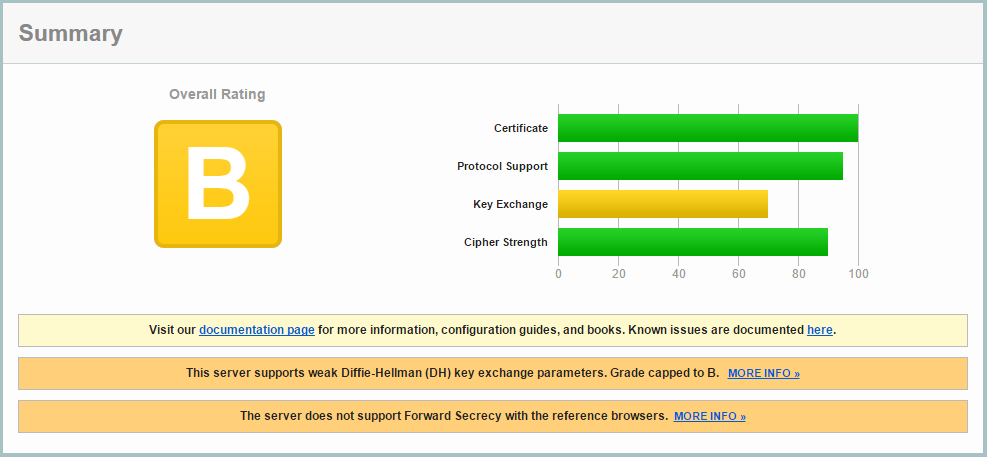

Now when you point your browser to your server, you should be seeing a pretty, greenish browser bar. Go to ssllabs.com and enter your hostname in the “test server” test. Looks like out of the box, we already get an B rating!

Let’s see what first step we can take to improve our rating.

Forward Secrecy and Diffie-Hellman

The orange bars mention two interesting features: Forward Secrecy and Diffie-Hellman. If you are unfamiliar with the general approach of the TLS Handshake, check out Wikipedia which has a pretty good explanation.

As you will see in that explanation, the client and server together come up with a common master secret. This secret is then used after the handshake to encrypt and decrypt the communication using a symmetric encryption approach such as AES. However, without Diffie-Hellman, the master secret is transmitted encrypted with the public key. Therefore, only the one with the private key can figure out the master secret. This means that whenever this key is compromised, earlier traffic that was recorded can potentially be decrypted using that private key. Then, with the master secret now available, the entire following communication can also be decrypted. In other words: even though your communication can not be read today, it can possibly be read in the future.

The idea of forward secrecy is that the client and server together generate a key without ever transmatting this key directly. In addition, this key is destroyed at the end of each session. This is possible through some smart but not that hard to understand mathematics (again, check out Wikipedia if you are interested). Therefore, if at anytime in the future the private key is compromised, even through the TLS handshake may be read, the master secret will not be found and further communication can not be decrypted.

Fixing the “weak keys”

Let us begin by fixing the issue mentioned in the top orange bar. Diffie-Hellman re-uses some numbers for creating a master key with each connection. These numbers are extremely big prime numbers and can take a while to be calculated, which is why they already need to exist. Many webserver installations reuse the same base numbers. A vulnerability known as the Logjam attack discovered that is is relatively easy for a large organization such as the NSA to eaves drop on servers that use these numbers. This means that if you re-use the same numbers as many other webservers do (read: the defaults), it becomes more easy to eaves drop on your communication. Not changing the default keys is therefore similar to not changing the default password for your MySQL, Redis, or whatever installation. If you want to know more about the exact maths, read this Stackexchange post.

Conclusion: we will generate our own Diffie-Hellman parameters! This is really easy and can also be done using OpenSSL:

openssl dhparam -out /etc/ssl/dhparams2048.pem 2048

The “2048” in the filename is not exactly required, but I like it as I can easily see the key size this way. It’s the 2048 at the end of the command that tells it exactly how large the key should be. You can also use a 4096 key, which is even more secure. However, today 2048 should already be secure enough and will give a performance improvement compared to 4096 bits.

Running the OpenSSL command will take a few minutes. Next, we’ll configure Nginx to use these parameters. Add the following line to your Nginx configuration:

ssl_dhparam /etc/ssl/dhparams2048.pem

Fixing “Forward Secrecy not available for reference browsers”

Now, let us look at the second orange bar visible in our SSL Labs report. On that same page, if you look at the “Cipher Suites” list a bit lower, you will see which suites have Forward Secrecy (FS) and which don’t. If you didn’t yet restart your Nginx configuration and re-test it on SSL Labs after the previous change, it will also show you that the parameters are weak. As you can see, a lot of cipher suites are weak. I won’t go into the exact detail of what they mean as this is worthy of a blog post an sich, but we only want those cipher suites that have Diffie-Hellman enabled for Forward Secrecy. These cipher suites begin with “TLS_DHE” or “TLS_ECDHE”, where “DHE” stands for Diffie-Hellman Exchange.

As we won’t dive into the cipher suites for now, a big help is the Mozilla SSL Configuration Generator. Here, click Nginx and the “intermediate” settings, and find the “ssl_ciphers” setting in the configuration below which, at the time of writing, is as follows:

ssl_ciphers 'ECDHE-ECDSA-CHACHA20-POLY1305:ECDHE-RSA-CHACHA20-POLY1305:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256:ECDHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:DHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256:DHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-SHA256:ECDHE-RSA-AES128-SHA256:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-SHA:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA384:ECDHE-RSA-AES128-SHA:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA384:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA:DHE-RSA-AES128-SHA256:DHE-RSA-AES128-SHA:DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA256:DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA:ECDHE-ECDSA-DES-CBC3-SHA:ECDHE-RSA-DES-CBC3-SHA:EDH-RSA-DES-CBC3-SHA:AES128-GCM-SHA256:AES256-GCM-SHA384:AES128-SHA256:AES256-SHA256:AES128-SHA:AES256-SHA:DES-CBC3-SHA:!DSS';

Finally, we’ll set “ssl_prefer_server_ciphers” to yes on (Update 21/10/17: changed “yes” to “on” after a comment from Özgür Kazanççı), so that we can pick the most secure cipher suite instead of letting this be handled by the client:

ssl_prefer_server_ciphers on;

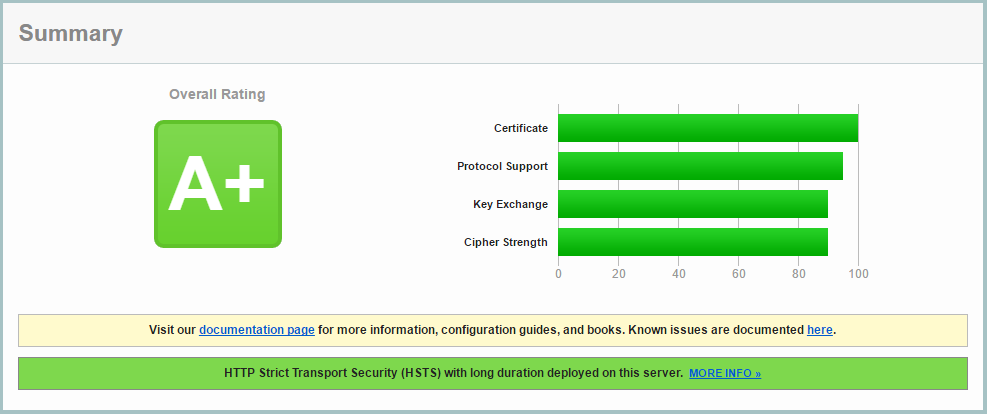

Make the changes to your configuration, restart nginx, and re-run SSL Labs. As you will see, we are now already at a pretty great A rating. Only one more step towards A+!

Achieving the A+ SSL rating

Unfortunately, SSL Labs does not clearly show what more needs to be done to get the A+ rating. Luckily, it’s not hard: we need to add the HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) header. In short, this header tells the client that this website should always be visited through HTTPS. This means that, after a first visit from a client to the server, subsequent visits to any http pages will be converted by the browser to https before any request is made. This saves us some round trip time and increases security, especially against the common protocol downgrade attacks. We can add this protocol to our configuration with the following line;

add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload" always;

The 31536000 seconds are roughly around a year. Yes - the browser will remember for a year that it should always visit your website through HTTPS. If, for any reason, you want to stop supporting https for your website, you will have a problem with browsers that have already received this header. Would you redirect any https traffic back to http, such browsers would redirect again to https resulting in an infinite loop. Therefore, if you are just playing around with SSL and aren’t sure you will keep it for your website, don’t enable HSTS for that website.

The includeSubDomains setting tells the browser to also enable HSTS for subdomains. I will discuss the preload setting in the next section.

Finally, the “always” after the header contents tell Nginx to provide this header with every possible response code, instead of only for the “200, 201, 204, 206, 301, 302, 303, 304, or 307” status codes.

Great. Reload Nginx and re-test your website in SSL Labs to see that much wanted A+ rating! Isn’t it pretty?

Taking it even further

Even though we already achieved the A+ rating, there is some more we can still improve. Looking at the “Protocol details” section in the SSL Labs report, we can still see one more red flag concerning “session resumption”. In addition, we will enable OCSP stapling and HSTS preloading.

HSTS preloading

With HSTS a browser will directly transform subsequent http requests to https. But, we can even go one step further. With the first http request a browser is still potentially vulnerable, so how can we tell a browser to never visit a website through http before it ever went to that website? This is exactly what HSTS preloading is for. By submitting your website to the HSTS preload list, you tell browsers to never visit your website through http. You can see if this is enabled by checking the “HSTS Preloading” key in your SSL Labs report.

Session resumption

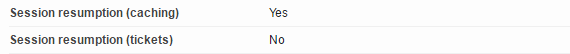

With session resumption, the server specifies some information to the client during the initial TLS handshake. In a second connection, the client can then use this information to skip the entire TLS handshake and immediately have a secure connection setup. This saves us some round trips during subsequent connections and therefore increases the performance for your users.

There are two ways that session resumption can be achieved. With the caching method a session ID is generated by and stored on the server. This ID is communicated to the client during the Server Hello. With the tickets method the entire secure connection state is stored on the client side. Session tickets have some security concerns, so considering that we have a choice here, let’s just enable session ID’s and disable session tickets. We can do this as follows;

ssl_session_timeout 1d;

ssl_session_cache shared:SSL:50m;

ssl_session_tickets off;

We store the session ID’s for 1 day. The cache is an in-memory cache, meaning the contents are never actually written to disk. The size of the cache is 50MB. One MB can store around 4000 sessions, so this should be more than enough for most servers. Be sure to check for the following properties in your SSL Labs test:

OCSP stapling

How does a browser know the certificate provided by a server is not revoked? With each certificate a browser receives, it performs a request to a Certificate Authority (CA) to check whether this is the case. This causes extra waiting time and it decreases security: when the CA check times out the browser will silently ignore this and load the website. In addition, it compromises privacy as the CA can keep track of what website is being accessed by who.

Instead of the browser checking the status of the provided certificate, we can have our server check this on a regular interval using the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP). During the TLS handshake, the server will sent the status of its certificate to the client (it is “stapled” with the request). The client can check the validity based on only the extra, stapled content.

Add the following lines to your configuration to enable OCSP stapling:

ssl_stapling on;

ssl_stapling_verify on;

resolver 8.8.8.8 8.8.4.4 valid=300s;

ssl_trusted_certificate /etc/ssl/example.com.trusted.pem;

The last line is a reference to a file that includes all trusted certificates (therefore, including the root certificate). This list is never sent to clients but instead used mainly for OCSP. Finally, we need the resolver configuration setting so that Nginx knows how to resolve DNS queries. We simply use the Google nameservers for this.

Conclusion

Even though it was quite a bit of information, I hope everything made sense and that you are now more confident about setting up SSL for your website. The entire contents of the created SSL configuration in this post can be found on my Github repository.

Let me conclude with some great resources I used and that you can also use for further understanding SSL:

- Mozilla SSL Configuration Generator. Here you can get a secure configuration file for a multitude of servers. You can use this as a base for your own configuration.

- Istlsfastyet.com. Information about setting up SSL with the best performance.