Table of Contents

Secret management is one of those security topics that is often an after-thought while designing systems. Passwords are set up manually, shared through non-secure methods such as e-mail or Slack, and password rotation is often neglected because it’s time-consuming and error-prone.

This is a shame because with some effort, secret management can definitely be automated. If done properly, less manual work is required to build and maintain applications, and of course security is increased reducing risk.

In this blog post I’ll discuss the design decisions that must be made while constructing a secret management automation solution. In addition I’ll share a simple utility that can be used to deploy secrets from AWS Parameter Store to an EC2 instance. This utility is based on a related blog post by AWS, but generalised to make it more useful for pretty much any application that has secrets stored in parameter store.

Secret management 101

Proper secret management allows you to safely and securely store secret values and (binary) files (such as passwords, tokens, license files, e.t.c.) in a central repository or system. Through Access Control Lists (ACL), only specific entities can retrieve the (decrypted) values of these secrets. If an application must retrieve the password for a MySQL database, only that application must be allowed to retrieve that value, even with other applications or users using the same secret management repository or system.

Another important requirement of such a system is an audit log. You will want to know who or what accesses (or fails to access) secrets, and when. In addition, password rotation is a key requirement. Passwords can easily be leaked, either by people or by applications (e.g. through dumps of error traces, logs, e.t.c.). As its pretty much impossible to prevent this 100%, proper key rotation must be implemented to be sure that any leaked passwords are valid for only a limited period of time.

This is also why automation is so important. With proper automation, rotating passwords every month, week or even every day becomes possible.

What exactly does it mean to “manage” a secret? Let’s say you set up a MySQL database and you configure an application user _appuser that can SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE in that database. The _appuser user is of course created with a password that needs to be configured in two or three different locations;

1. The MySQL database. The user + password configuration must of course be configured in the MySQL database.

2. The application. The application that is going to authenticate with this user must be able to retrieve the password. As we’ll see in a bit, there are multiple ways to set this up.

3. Optionally: a human user. In some situations, it might be desirable to give people access to the password as well. Ideally and very much recommended, this would be the same system as where the application retrieves the password from. If for some reason this is not possible, you will need to store the password in a second location as well (which opens up troubles such as keeping the 2 sources of truth in sync, and it doubles the possibility of misuse of the passwords). Human access is typically required when a secret must be used by an entity outside of the environment where the secret management utility exists. Such sharing is then done, for example, by sending out an e-mail with a one-time link that gives access to the password only once.

In the next few sections I’ll focus on design decisions for getting the secrets available to the application. I’m going to make the assumption that your code resides in a VCS system and that this code is deployed to a server in an automated fashion.

Placeholders vs. encrypted values

Placing decrypted values - plaintext secrets - in your source control repository is definitely a no-go for security reasons. The question then is whether to put encrypted values in your repository, or simply placeholders referencing an external secret management system.

One example of storing encrypted values is hiera-eyaml for Puppet. This utility allows you to specify encrypted values in your Puppet configuration. When a machine is provisioned with Puppet, the Puppet master will decrypt the values using the private key and configure the machine using the decrypted values. The encrypted values can then safely be stored in your Version Control System (VCS). Similar utilities exist for Ansible and Chef.

A benefit of having the encrypted value in your repository is full transparency close to your source code. Whenever the secret is changed and a new encrypted value is generated, that value will be updated in your repository through a commit. Changing a secret to a new value is exactly the same as making any other changes to the source code. No external repository or system is required to store these secrets.

With the second approach of using placeholder values, a key referencing a secret stored in an external system is used instead. The utility I created and explain later in this blog post is an example of using placeholder values.

One benefit of using placeholders is easier automation. If you have a system that automatically refreshes secrets, the application using that secret must also receive the new value. When this value is stored in a VCS, possibly as part of a configuration file (such as config.php or config.ini), some logic is required to update the specific string. When using a placeholder value, the VCS doesn’t need to be touched but instead, a single value in the global secret management system must be updated.

Another advantage is that all secrets are kept in a single place. This makes it much easier to get an audit of who accesses and changed secrets. If secrets are stored in different formats in different VCS repositories, it’s hard to get a single overview of all managed secrets.

I’m certainly in favour of the placeholder approach as it gives you much more flexibility in regards to automation. And automation should be the main goal for any (operations) engineer, right?

Runtime vs. bootstrap time

The second decision we need to think about is where to put the responsibility to either (based on the decision in the previous section);

- Decrypt the encrypted value stored in your VCS;

- Fetch the secret referenced by the placeholder key.

We have a few options here. First, we can add this logic to the bootstrapping of your system or during the deployment of your application to that system. If you run pure immutable infrastructure, these two options are essentially the same option. This is typically the choice picked for Docker containers, as secrets are injected through environment variables. When those secrets change, a new Docker container needs to be spawn with the changed secrets injected.

As mentioned in the previous section, configuration management tools such as Puppet and Ansible also support management of secrets. These tools can be part of the bootstrapping phase and do the work for you. If you run Puppet on an interval on your systems to prevent configuration drift, or if you have a mechanism to run Ansible playbooks against running machines, you can use these tools to update secrets on live machines.

When you run VMs to which you deploy application updates, you can put the logic of changing secrets in those deployments. For example, during a deployment you also update a config.php or config.ini file to hold the secrets, or you set some environment variables. Since the deployment already changes your system, it makes sense to also deploy any updates to secrets while you’re at it. At the other hand, you’re now mixing up the responsibilities of your deployment pipeline as it now has an extra purpose. The example utility I dive into at the end of this blog post uses this approach as it’s very simple to set up.

The second option is to have the application manage the secrets itself. When an application grabs, for example, the database password for the first time, it will see the secret is not yet decrypted or retrieved from the secrets repository (in the case of a placeholder). The application will then need to decrypt the secret or contact the secrets repository. This gives you a lot of flexibility since the application can control where to cache the secret for subsequent uses, how long to cache it, and you can build in mechanisms to force rotating a secret and fetching the latest version from a secrets repository. On the other hand, you’re essentially moving this responsibility to the application developers and increasing the work required to build and maintain an application.

The third and final option is to run a separate service that has the sole purpose of keeping the secrets on your system up to date. This removes the responsibility from your application and keeps the logic away from your deployments or cloud-init scripts. Of course, the downside then is that you need to run and maintain an extra service. One example here is to use consul-template linked to Hashicorp’s Vault. The secrets are stored in Vault and whenever they change (e.g. due to scheduled rotation), consul-template will pick up that change and put the new secrets on the system. Again, tools like Puppet and Ansible can be used for this as well by making sure these tools are triggered when a secret is changed.

Secret management utility

It’s really up to your specific use case which approach works best. In this section, I provide an example that shows one way of getting your secrets on your system. This example is specifically using AWS technology, but the idea and approach can definitely be used for other technologies. I wrote a simple utility function that works as follows;

- You put placeholders in a configuration file. These placeholders point to keys in AWS Parameter Store

- The utility is executed during a CodeDeploy deployment. Codedeploy is the managed deployment service from AWS. The utility is setup in a generic way thus it can be easily executed by other deployment tools

I’ve chosen placeholders as it eases automation (e.g. password rotation). Once a new password is generated and put in parameter store, a simple deployment fetches the new passwords and start using them. The secrets are decrypted before CodeDeploy places them on the machine. The application is completely unaware of how the secrets get on the system (loose-coupling) and can simply start using them. I like using the application deployment mechanism to update secrets as it gives you access to the machine and no additional mechanism is required, lowering overall complexity.

The utility can be found in my GitHub repository. It includes a CloudFormation stack that spins up an environment that you can use to test the utility. The actual replacement of the placeholders can be found in the ssm_replacements.py file. Based on a regex, it searches for patterns such as ${ssm:/path/to/key} and replaces it with the value retrieved from Parameter Store. A key that is not found will cause the script to fail with an error message: this can for example happen if a secret is not or wrongly configured in Parameter Store.

Take the following steps to fully give it a test-run;

- Clone the GitHub repository. If you are planning to deploy the stack in a different region than

eu-west-1, change the single parameter at the top of the CloudFormation file - Deploy the CloudFormation file either through the UI or with the following command:

aws cloudformation create-stack --stack-name codedeploysecretstest --template-body file://cloudformation.yaml --capabilities CAPABILITY_IAM - In the EC2 UI at AWS, find the Parameter Store section. Here, create a new parameter with the key

/myapp/password. Create a secret string with the default KMS key, and set whatever password you want (don’t specify a password that you actually use! The “secret” value is going to be visible for the entire world soon) - Deployment will take a few minutes. One of the first things that is created is the S3 bucket. Go to the S3 console and find the new S3 bucket - the name will start with

codedeploysecretstest-deploymentartifactsbucket- - .Zip the entire app directory. The easiest method is to cd to the

app/directory and runzip -r application.zip .. This ensures that all the files are located in the root directory of the ZIP file. Upload this file to the newly created S3 bucket. - With the following command, deploy the application to the EC2 instance through CodeDeploy:

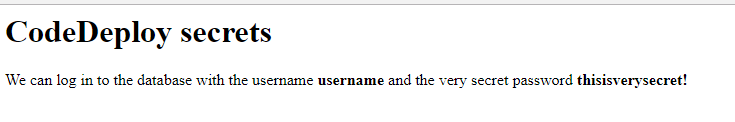

aws deploy create-deployment --application-name codedeploy-secrets-test --deployment-group-name testing --s3-location bucket=**[s3_bucket_name]**,bundleType=zip,key=application.zip - Using the public IP address or DNS entry of the EC2 instance, visit it in your browser and you should see something like the following:

Great success! This shows that whatever you specified as the password was successfully grabbed from parameter store during the CodeDeploy deployment. If you change the php files to grab any other keys from the store, you can easily use those parameters as well.

Feel free to use the utility as you see fit. Keep in mind that it output some debugging data in case you want to check the logs, including the passwords that it extracts from parameter store. Remove those print statements before you use it in production!

Conclusion

In this blog post, I first explained some Secret Management 101 theory. Keep in mind any requirements you have and think about the design options that I describe. Automation is definitely possible - and quite the fun undertaking - which I show through a simple utility that replaces any placeholders with real secrets from AWS Parameter Store.

While I run the utility during a CodeDeploy deployment, keep in mind that you can also run it in a cloud-init script or even recurring through a cron job or a configuration management tool. Feel free to use and change the script for your specific requirements. Have fun!