Table of Contents

The AWS Cloud Development Kit (AWS CDK) is a new framework for defining Infrastructure as Code (IaC) by AWS. It allows you to write IaC in a set of different languages. At the moment the following languages are supported: Javascript, Typescript, Python, Java, .NET. Support for other languages is coming.

Of course, other methods like CloudFormation and Terraform already exist to write IaC. Using these tools you write declarative code in YAML, JSON or the Hashicorp Configuration Language (HCL) in a mostly declarative state. These tools will also support some basic operators such as if-statements and for-loops. Especially HCL has many of these capabilities with the latest 0.12.0 release. However, it will always be different from using a “real” programming language. And it requires you to use a new tool, instead of using a language you already know.

The CDK is therefore closer to tools such as Troposphere and Pulumi. The main difference is that the CDK is an official tool from AWS (and will therefore, supposedly, only support AWS as a provider. But don’t quote me on that). What is also nice is that the CDK makes it easy to spin up “complex” resources such as a VPC or a database with “sane defaults”. In fact, AWS Security is also involved in the development of the CDK.

The CDK generates CloudFormation which is then deployed to AWS. This means that you get the full benefits of writing procedural code in a “normal” programming language of your choice, while also having the benefit of declarative CloudFormation which calculates the difference between the actual and desired state for you and applies the correct changes to get the environment in the desired state.

It’s important to note that the CDK is currently still in beta. Each release comes with a set of breaking changes. However, the intention of the developers is to get the CDK into a solid state that would minimize the amount of breaking changes with each release. Having worked with the CDK for a few months now, I only had to make small changes to my code after a new version was released (which is pretty much every week). I definitely don’t consider this to be a blocker for using the CDK. Also, since the CDK is open source, I was able to contribute a few small features that I was missing.

Of course, the best way to learn is by doing. To get a better feeling of how the CDK works, in this blog post we’ll deploy a serverless application to AWS using the CDK. We’ll also take a look at how we can get run our Serverless Lambda funtions locally using the CDK together with AWS SAM. Let’s get started!

Getting started with the AWS CDK

The easiest way to install the CDK is using NPM:

npm install -g aws-cdk

If you prefer not to use NPM, you can also check out the documentation for the manual installation.

Check that the CDK is properly installed using cdk --version. I’m using version 0.33.0 as I’m writing this post: keep in mind that feature versions may well include breaking changes that break the code in this blog post.

Create a new directory called serverless-cdk and initialize it with a sample CDK application using the following command:

cdk init app --language=typescript

If you want to follow along with this blogpost, be sure to use Typescript as well even if you prefer one of the other supported languages.

To download the dependencies for this project, run npm install.

The entrypoint of the application is found in the bin directory. Open up the serverless-cdk.ts file there (if you initialized the application in a directory with a different name, this file will have a different name).

#!/usr/bin/env node

import 'source-map-support/register';

import cdk = require('@aws-cdk/cdk');

import { ServerlessCdkStack } from '../lib/serverless-cdk-stack';

const app = new cdk.App();

new ServerlessCdkStack(app, 'ServerlessCdkStack');

This is all it takes to get a stack up and running. We first create a new CDK app and the add the ServerlessCdkStack to it. This stack is defined in the lib directory. Check out the serverless-cdk-stack.ts file in this directory. What you will find is an empty stack. To synthesize a CloudFormation stack from this Typescript code, run cdk synth. You will see a YAML file with only a CDKMetadata resource. Let’s add our first resource to this stack!

Since this is a Typescript project, the code we write will need to be converted to Javascript. In a new terminal, run npm run watch. This will watch for any changes to the Typescript code, and generate Javascript.

Now, below the line // The code that defines your stack goes here, add the following code:

const queue = new Queue(this, 'queue', {

queueName: 'queue'

});

Also, add the top of the file add the following import:

import { Queue } from '@aws-cdk/aws-sqs';

Finally, in the package.json file in the root of your project, be sure to add the following dependency in the dependencies object:

"@aws-cdk/aws-sqs": "^0.33.0",

Be sure to run npm install again to download the SQS dependency.

Now, run cdk synth again and note that the synthesized CloudFormation now contains a SQS queue:

queue276F7297:

Type: AWS::SQS::Queue

Properties:

QueueName: queue

Metadata:

aws:cdk:path: ServerlessCdk2Stack/queue/Resource

Nice! This CloudFormation will create a queue with the name “queue” as we have defined in the CDK. Assuming you have properly configured the AWS CLI on your system, you can now deploy this stack using the following command:

cdk deploy

Within a few minutes you will have an SQS queue deployed to your AWS environment. Let’s setup something more advanced next to see more of the capabilities that the CDK offers.

Building a serverless application

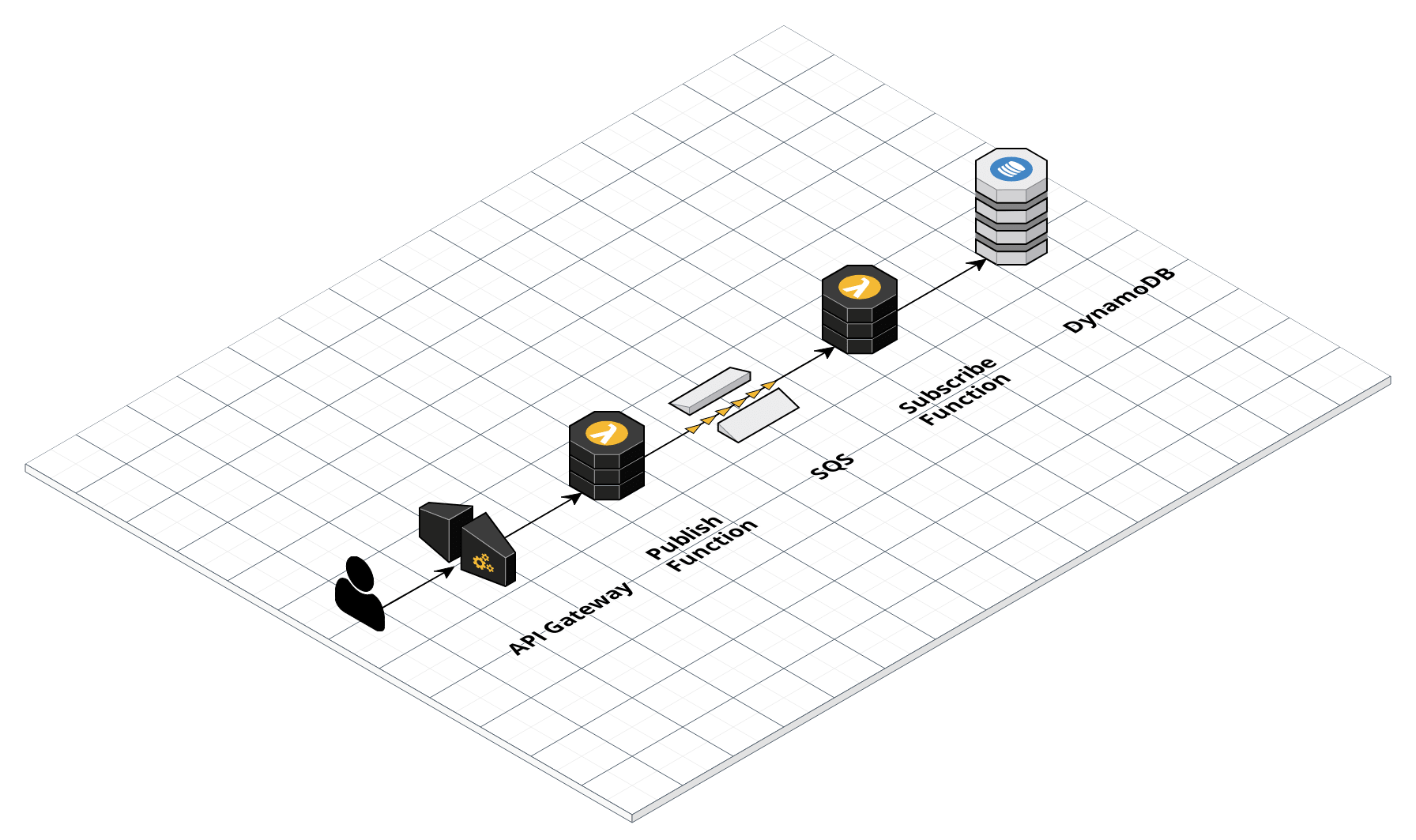

The application we’ll deploy is configured as follows:

We create an API Gateway endpoint that invokes a Lambda function. This Lambda functions chooses a random number between 0 and 10000, and posts this number to an SQS queue. Another Lambda function picks up this message, and puts the value in DynamoDB.

If you’ve worked with these resources before through IaC, you may remember the hassle of setting up all the IAM permissions (least-privilege, of course) for these resources to talk with each other. API Gateway will need permissions to invoke Lambda the first Lambda function. SQS also needs to the permissions the invoke the second Lambda function. In my experience, properly connecting these resources takes at least as much time - if not more - than configuring the actual resources.

In the AWS CDK, the code would look as follows:

import cdk = require('@aws-cdk/cdk');

import { Function, Runtime, Code } from '@aws-cdk/aws-lambda';

import { SqsEventSource } from '@aws-cdk/aws-lambda-event-sources';

import { RestApi, LambdaIntegration } from '@aws-cdk/aws-apigateway';

import { Table, AttributeType } from '@aws-cdk/aws-dynamodb';

import { Queue } from '@aws-cdk/aws-sqs';

export class ServerlessCdkStack extends cdk.Stack {

constructor(scope: cdk.Construct, id: string, props?: cdk.StackProps) {

super(scope, id, props);

const queue = new Queue(this, 'queue', {

queueName: 'queue'

});

const table = new Table(this, 'table', {

partitionKey: { name: 'id', type: AttributeType.Number }

});

const publishFunction = new Function(this, 'publishFunction', {

runtime: Runtime.NodeJS10x,

handler: 'index.handler',

code: Code.asset('./handlers/publish'),

environment: {

QUEUE_URL: queue.queueUrl

},

});

const api = new RestApi(this, 'api', {

deployOptions: {

stageName: 'dev'

}

});

api.root.addMethod('GET', new LambdaIntegration(publishFunction));

const subscribeFunction = new Function(this, 'subscribeFunction', {

runtime: Runtime.NodeJS10x,

handler: 'index.handler',

code: Code.asset('./handlers/subscribe'),

environment: {

QUEUE_URL: queue.queueUrl,

TABLE_NAME: table.tableName

},

events: [

new SqsEventSource(queue)

]

});

queue.grantSendMessages(publishFunction);

table.grant(subscribeFunction, "dynamodb:PutItem");

// EDIT June 2th, 2019: after feedback from the AWS CDK team I learned about the above

// "grant" methods to extends the permissions of the Lambda functions. It's much more

// readable than the earlier code I had which you can see below.

// publishFunction.role!.attachInlinePolicy(new Policy(this, 'lambdaPublishToSqsPolicy', {

// statements: [

// new PolicyStatement(PolicyStatementEffect.Allow).addAction('sqs:SendMessage').addResource(queue.queueArn)

// ]

// }));

// subscribeFunction.role!.attachInlinePolicy(new Policy(this, 'lambdaWriteToDynamoDbPolicy', {

// statements: [

// new PolicyStatement(PolicyStatementEffect.Allow).addAction('dynamodb:PutItem').addResource(table.tableArn)

// ]

// }));

}

}

In the last few lines we add some permissions to both Lambda functions so that they can put messages in respectively SQS and DynamoDB. However, all the other permissions are automatically configured by the CDK using the least-privilege principle. It’s import to realize that the objects (such as the Function object) we use are not 1-to-1 mappings to a CloudFormation resource. It’s a higher-level resource - the CDK calls this a “Construct” - thas makes it easy to create a Lambda function by setting sane defaults for most properties. You can also use objects that directly map to CloudFormation resources (e.g. the CfnResource function), but in general you shouldn’t need these resources.

Next, create a new directory called handlers in the root directory of the project. That is where we will store the code for the two Lambda functions. In this directory, create two directories: publish and subscribe. In both these directories, create a file called index.js. The directory structure should now look like this:

handlers

-- publish

---- index.js

-- subscribe

---- index.js

In the index.js for the publish function, paste the following code:

const aws = require('aws-sdk');

const sqs = new aws.SQS();

exports.handler = async (event) => {

const randomInt = Math.floor(Math.random() * Math.floor(10000)).toString();

const params = {

QueueUrl: process.env.QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody: randomInt

};

await sqs.sendMessage(params).promise();

return {

statusCode: 200,

body: `Successfully pushed message ${randomInt}!!`

}

}

In the index.js for the subscribe function, paste the following code:

const aws = require('aws-sdk');

const dynamodb = new aws.DynamoDB();

exports.handler = async (event) => {

for (const record of event.Records) {

const id = record.body;

console.log(id);

const params = {

TableName: process.env.TABLE_NAME,

Item: {

"id": {

N: id

}

}

}

await dynamodb.putItem(params).promise();

}

return;

}

Both functions are pretty self-explanatory. I didn’t add any error handling and such to keep the code as simple as possible.

In order to execute the CDK code, make sure that the package.json files contains the following dependencies:

"dependencies": {

"@aws-cdk/aws-apigateway": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/aws-lambda": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/aws-lambda-event-sources": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/aws-sqs": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/aws-iam": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/aws-dynamodb": "^0.33.0",

"@aws-cdk/cdk": "^0.33.0",

"source-map-support": "^0.5.9"

}

Now, run cdk synth again and notice that a big piece of YAML is generated for you. If you have experience with CloudFormation, you will notice that many permissions are automatically created that you would otherwise have to code yourself. It’s great how the CDK helps in writing IaC with much less lines of code compared than CloudFormation.

To deploy this serverless application, run cdk deploy. It will take a few minutes to deploy all these resources. At the end of the output you will find a URL to the API Gateway endpoint. Hit this endpoint in your browser and you will see a message that a specific number has been successfully published. Check out the Lambda logs and the contents of the DynamoDB table that this number his progressed all the way through the serverless application.

Next up, let’s see how a development workflow would look like as we make changes to this stack and to the Lambda source code.

Local development

I always consider easy local development a key feature of any tool I’m using as this allows me to get feedback much more quickly. I want to have easy and quick feedback on the changes I make to my infrastructure code: is it going to be applied in the way I expect it to? Also, let’s see how we can run and test the Lambda functions locally before pushing them to AWS.

Displaying CloudFormation changes

Let’s say that we change the SQS queue name from “queue” to “myawesomequeue”. In the serverless-cdk-stack.ts file, change to the queue configuration so that it looks like the following:

const queue = new Queue(this, 'queue', {

queueName: 'myawesomequeue'

});

Running cdk diff will then tell us exactly what changes would be applied to AWS:

[~] AWS::SQS::Queue queue queue276F7297 replace

└─ [~] QueueName (requires replacement)

├─ [-] queue

└─ [+] myawesomequeue

It’s great that we can directly see that this is going to replace our queue. This means that any messages currently in the queue would be lost: definitely something to keep in mind when pushing this change.

If we instead were using plain CloudFormation from the command-line, we would first have to create a change set, wait for it be to created and then describe the change set. The CDK makes this much easier to execute.

Terraform users will see that this is very similar to the terraform plan command. I’m happy that there now is an easy way to get this output for CloudFormation stacks.

Running Lambda locally

AWS already provides a great tool for running and debugging our Lambda functions locally: AWS SAM CLI. The SAM CLI allows you to spin up a local Docker environment that mimics the AWS Lambda environment. SAM CLI then runs your Lambda function within this container. Let’s see how we can use use the SAM CLI together with the AWS CDK.

If you haven’t installed the SAM CLI yet, check out the installation instructions to do so. If you’re on Mac, you can use the following commands to install SAM CLI:

brew tap aws/tap

brew install aws-sam-cli

Check that you have properly installed the SAM CLI by running sam --version. At the time of writing, the version is 0.16.1.

The SAM CLI needs a CloudFormation template that contains the Lambda function configuration, and tells the SAM CLI where to find the source code for the Lambda function. We’ve seen before that we can generate CloudFormation using cdk synth. SAM by default looks if a file called template.yaml exists, so generate this file with the following command:

cdk synth --no-staging > template.yaml.

Let’s look at a simplified CloudFormation Lambda function that the CDK generates:

publishFunction0955FBF8:

Type: AWS::Lambda::Function

Properties:

Code:

S3Bucket:

Ref: publishFunctionCodeS3Bucket2C44CE56

S3Key:

Fn::Join:

- ""

- - Fn::Select:

- 0

- Fn::Split:

- "||"

- Ref: publishFunctionCodeS3VersionKey0A26AC56

- Fn::Select:

- 1

- Fn::Split:

- "||"

- Ref: publishFunctionCodeS3VersionKey0A26AC56

Handler: index.handler

Runtime: nodejs10.x

...

Metadata:

aws:cdk:path: ServerlessCdkStack/publishFunction/Resource

aws:asset:path: /Users/sander/Projects/serverless-cdk/handlers/publish

aws:asset:property: Code

SAM CLI uses the Runtime property to spin up a Docker container with the correct runtime environment. The Handler property is then used to know which function to execute in which file (in this case: the function handler in the file index.js).

The Metadata property is then used to learn where to find the source code of the Lambda function locally. When we run cdk synth --no-staging, the CDK does not stage the source code in a new, temporary directory. This prevents your directory from clogging up with temporary directories, and makes the CloudFormation a bit easier to read. Also, when debugging your code using breakpoints and such, you don’t have to open the staged code in the temporary directory to set these breakpoints. Finally, because of the --no-staging flag, you will not need to re-run cdk synth after you make changes to your Lambda code to test the code - I’ll get back to this in a bit.

This Metadata feature was specifically built into SAM CLI for applications such as the AWS CDK. More information about this can be found in the SAM CLI documentation.

Let’s run our publishFunction Lambda function locally. This function takes the QUEUE_URL environment variable that is injected by CloudFormation. The value of this variable is a reference to another CloudFormation resource (the SQS queue). As AWS SAM can not interpolate this value - as it does not actually deploy the stack - it will keep the value of this variable empty. We can instead use an override parameter file to manually define the value of this environment variable.

Create a file called environment.json and fill it with the following contents:

{

"publishFunction0955FBF8": {

"QUEUE_URL": "https://sqs.[AWS_REGION].amazonaws.com/[ACCOUNT_ID]/queue"

}

}

Replace the AWS_REGION and ACCOUNT_ID placeholders with the correct values. You can also log in to the AWS SQS console and lookup the QueueUrl value of the createdd queue there. The logical ID of your Lambda function (publishFunction0955FBF8) should already be the same if you copied the CDK code above.

We can now invoke SAM like this:

echo '{}' | sam local invoke publishFunction0955FBF8 --env-vars environment.json

The publishFunction0955FBF8 is a reference to the logical ID of your function. If SAM complains that it can not find this function, check out the template.yaml file and find the logical ID for the Lambda publish function.

Now, change the code of the Lambda function. For example, change the message to output Successfully pushed message ${randomInt}!!! (add some exclamation marks). Run the invoke command again and you will see that SAM has picked up the code change and will report the new message. Would we not have used the --no-staging flag with cdk synth, this would not have worked as we are not editing the staged code which CloudFormation references.

The development experience is now pretty great: run cdk synth --no-staging > template.yaml again after having made changes to the CDK code. If you make any changes to the Lambda code, simply re-run sam local invoke to test your changes to the function.

Conclusion

The AWS CDK is a great tool that allows you to write Infrastructure as Code in a number of different programming languages. The CDK made me realize how liberating it feels to write IaC in a “proper” language instead of YAML, JSON or yes, even HCL. Granted, perhaps I never gave tools like Troposhere and Pulumi a fair chance. But the reality is that with the CDK I did, and I’m definitely enjoying it.

Just consider what you can do with writing proper, re-usable pieces of code such as abstractions for sets of AWS resources. And imagine properly (unit) testing these pieces just like you would with any other piece of code. While this is definitely possible with the alternative tools I mentioned earlier, doing it in a programming language that you already know makes it so much easier.

Give it a shot!